This English Professor Reviving Medieval Egyptian Cooking

From 13th century sour orange chicken to Andalusian milk tharida, Professor Daniel Newman recreates recipes preserved in medieval manuscripts.

Every week, from his kitchen in Durham, a town in northeast England known for its Gothic cathedral and ancient university, Professor Daniel Newman recreates recipes preserved in medieval Arabic manuscripts. His Instagram account, ‘Medieval Arab Cooking’, showcases historical dishes like 13th-century Aleppine sour orange chicken, Andalusian milk tharida with mutton, and vegan samosas devised by Sultan Saladin's private physician, bringing to life the rich culinary traditions of the medieval Arab world.

“I’m partial to the fruit stews—cherry chicken, limoniyya—but my favorite is an ancient dish originally from Iran” Professor Newman tells me, as my own stomach starts to rumble. It's now evening and other than a foul and egg sandwich hastily devoured over lunch I have eaten nothing all day. “It’s a layered pudding of flatbreads between each layer of which are lain fruit, nuts, and sugar, baked with chicken on top so that the basting juices soak into the bread” he elaborates.

Chair of Arabic Studies at Durham University and a cultural historian, Professor Newman is among the world’s foremost authorities on Middle Eastern food history, with his interest in the subject tracing back to his earlier research into medieval Islamic medicine.

“You can’t really study Islamic medicine without studying food,” Newman explains. “Medieval Arabs adopted a holistic approach to health, rooted in ancient Greek traditions, where diet was central. For instance, freshly eaten catfish was believed to purify the windpipe, while chard with mustard was used to treat liver blockages, and highland olives were thought to protect against sciatica.” Newman notes.

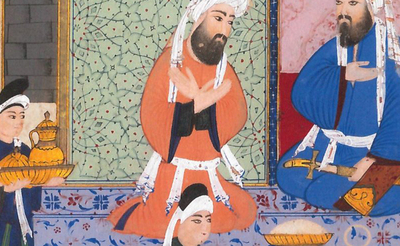

In 2021, Professor Newman published a translation of a 15th-century Egyptian cookbook, rendering its beautifully florid Arabic title, Zahr al-ḥadīqa fi ‘l-aṭima al-anīqa, as A Sultan’s Feast. The book contains around 330 recipes, ranging from bread-making and omelets to sweets and pickling, and also offers a variety of practical cooking tips and tricks.

Little is known about the book’s author, the scholar Ibn Mubarak Shah, who lived in Cairo during the turbulent twilight of the Mamluk Sultanate, on the eve of Egypt’s conquest by the Ottomans. What we do know comes from tantalizing details gleaned from the manuscript itself, the only extant copy of which is held at the Gotta Library in Erfurt, Germany.

“The book was compiled as a sort of recipe book for use in Mubarak Shah’s personal kitchen just as you and I may keep a note of recipes that we like and as such provides some tantalizing insights into his circumstances.” Newman shares. “For example, not being a particularly rich man, he includes elite recipes befitting the household of a prince but as a humble scholar suggests replacing expensive ingredients like the nutmeg and cinnamon, and using something cheaper like acacia instead.”

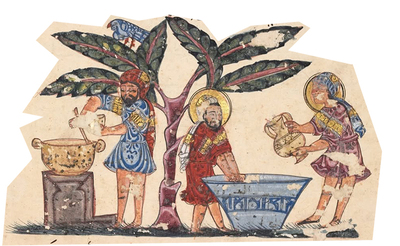

The Sultan’s Feast fits into a broader tradition of medieval Arabic cookbooks, which long predated similar works in Europe. The earliest known is the 9th-century Kitab al-Tabikh ("The Book of Cooking") by Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq, whose intricate recipes full of exotic ingredients are a written record of the lavish court banquets of the Abbasid caliphate. Some of these cookbooks were practical kitchen guides, while others, like a 13th-century gilded manuscript that once belonged to the imperial library of the Ottoman Sultans, served more as status symbols.

For Professor Newman, recreating the recipes began first as a hobby but developed into something else. “The recipes were written by chefs for chefs and often lack details like precise measurements. By cooking them, I’ve been able to fill in those gaps, which has informed my understanding of the texts. Now, having cooked thousands of recipes I can almost instinctively tell what they intended.” Newman notes.

However, sourcing some of the weird and wonderful ingredients included in the manuscripts can be a challenge in a small English town. “Whenever I travel to the Middle East, I always make a point to visit an attar (a Middle Eastern spice shop) to restock my spice drawer. Over the years, I have accumulated musk (an aromatic substance produced from glandular secretions of a type of deer) from the Souq al-Attareen in Tunis, ambergris (the solid waxy bile of sperm whales), and mastic (the bitter yet refreshing resin from the mastic trees of the Greek island of Chios).”

- Previous Article Pop, Sip & Glow With Suntop’s New Pink Lemonade

- Next Article Sink Your Teeth Into Egypt's Historic Fast Food Chains

Trending This Month

-

Jan 22, 2026